Countries across the globe like to talk a big game about developing their domestic shale oil and gas resources and sometimes utter lofty expectations of energy independence. Progress, however, has been very slow.

The following map by the World Resources Institute (WRI) illustrates locations of the 20 countries with the largest shale gas and tight oil resources, while incorporating WRI analysis of the level of water stress across every play in each country. Notably, the potential of shale across the globe depends in no small measure on water supply.

Source: World Resources Institute (WRI)

For shale gas, the WRI found that “plays in 40 percent of those countries face high water stress or arid conditions: China, Algeria, Mexico, South Africa, Libya, Pakistan, Egypt, and India.

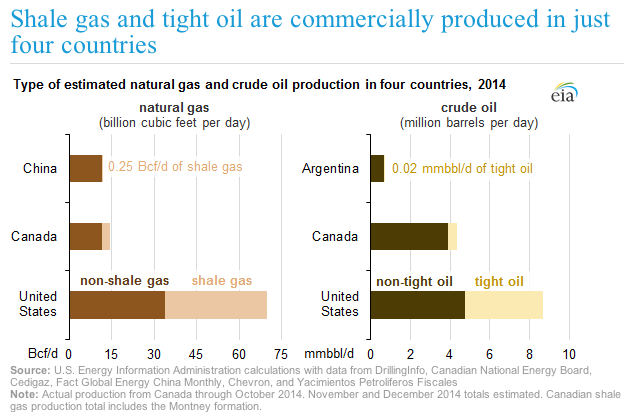

Moreover, it may come as a surprise that – according to the EIA – only four countries in the world – the US, Canada, China, and Argentina – actually produce commercial volumes of either natural gas from low-permeability shale formations (shale gas) or crude oil from tight formations (tight oil). No surprise, however, is that the US is “by far the dominant producer of both shale gas and tight oil” thereby in a sense monopolizing the required hydraulic fracturing technology and operational expertise needed to extract these resources. No country has the extensive equipment inventory – rigs, well completion tools, etc. – found in the US.

Source: EIA

Source: EIA

According to the EIA, Sinopec and PetroChina reported “combined shale gas output of a [mere] 0.163 Bcf/d, or 1.5% of total natural gas production,” from fields in the Sichuan Basin. Faouzi Aloulou of the EIA also elaborates on why China and other countries lag behind in commercial shale development of the type demonstrated in the US. Factors to consider include the “ability to rapidly drill and complete a large number of wells in a single productive geologic formation,” accompanying logistics as well as infrastructure including “the drilling and completion processes, the manufacturing of drilling equipment, and the distribution of the final product to market.” Additionally, other so-called “above the ground factors such as ownership of mineral rights, taxation regimes, and social acceptance” also play significant roles in the success of US shale development.

The American Enterprise Institute (AEI) concurs and hails the resilience of the US political-economic system, noting the US possesses the ‘complete package’ or – in AEI’s words from its latest report “Too Much Energy? Asia at 2030,” – “the best possible combination for innovation in energy [comprising the necessary] natural resources, well-defined property rights, an open and competitive industrial structure, and deep capital markets.” Conversely, while China possesses abundant shale reserves it lacks most of the determining factors that seem indispensable for a successful shale revolution in China.

Source: AEI, Infographic by Olivier Ballou.

In sum, given that “61 percent of shale resources [in China] face high water stress or arid conditions” (for that, read WRI analysis here), water stress may turn out to be in China’s case the decisive constraining factor explaining why a full-blown US-type shale revolution in China is not in the offing. Besides, large shale reserves happen to be situated in the vast Sichuan Basin, an area of high earthquake risk.

The Sichuan Basin (China)

Source: California Institute of Technology (Caltech), Tectonics Observatory

In this context, it may also be instructive for Chinese energy regulators to monitor any developments about frequent earthquakes surrounding the Dutch Groningen gas fields – the largest in Europe – and to take the right lessons from it if there is a political will to do so. As reported by Reuters, the Dutch Safety Board found that the operators and the Dutch government ignored the “danger of earthquakes caused by gas extraction” for decades. Anthony Deutsch of Reuters writes that operations have “resulted in increasingly strong earth tremors, some measuring as much as 3.6 on the Richter scale.”