“What would our energy system look like if the move to a low-carbon society wasn’t left to governments and big energy companies but was instead led by civil society?” – asks Dr. Stephen Hall, a Research Fellow in energy economics and policy at the University of Leeds (UK). Hall is co-author of a new report titled “Distributing Power – A Transition to a Civic Energy Future”. The idea here is that “communities, citizens and local authorities together can form a “civic” energy sector that could revolutionise the way” electricity is generated, transported and consumed.

This research was carried out by the ‘Engine Room’ of the EPSRC-funded ‘Realising Transition Pathways (RTP)’ consortium, made up of researchers from across nine UK universities.

The report explores a scenario in which the UK energy system follows a “pathway of distributed energy provision led by civil society” – the so-called “Thousand Flowers” pathway, which is characterized by the incorporation of new stakeholders into the energy sector on the supply side of power generation. Naturally, this has to be viewed by large utilities as an assault on their traditional vertically-integrated business model. In this context, three general transition pathways for energy systems have to be distinguished. Each pathway exhibits a “specific technological mix, institutional architecture, and societal drivers”:

- Central Co-ordination:

The role of the state is central in the transition process by actively steering and eventually delivering the transition.

- Market-based Rules:

Within the context of a broad policy framework, the state allows for and encourages competition in the marketplace with private companies envisioned to deliver safe, secure, sustainable, and affordable energy.

- “Thousand Flowers”:

In this pathway civil society’s role in delivering distributed low-carbon power generation is envisioned to be greatly expanded thereby de-emphasizing both government- and market-led pathways. In a sense, this also marks the renunciation of the leadership of the traditional stakeholders in the energy sector.

The third pathway – the growth of a civic energy sector – would force the big traditional utilities to realign their business models to be able to provide new services to the emerging class of “prosumers,” while the old system of paying for energy by volume (units) would slowly become obsolete. Moreover, the research consortium notes that the third pathway is different in the sense that traditional roles of the government, the energy industry, and civil society are turned upside down:

“Central to the achievement of the Thousand Flowers pathway, is the proliferation of local energy schemes (LES) delivered by a civic energy sector, which by 2050, has grown to supply 50% of final electricity demand. The remaining 50% of electricity demand is met by highly efficient gas plant with carbon capture and storage (CCS), offshore wind, nuclear, and hydro connected to the national transmission grid.”

The envisioned large expansion of the ‘civic’ energy sector, however, is premised on “smart grid technologies, new business models, and institutional structures all of which transform(s) the way energy is financed, distributed, licensed, and supplied to consumers,” the researchers warn. What basically happens is that “the generation mix will evolve from a landscape dominated by large power generators providing predictable and mostly flexible electricity generation, to a scenario with a significantly greater proportion of highly variable and less flexible generation.” Notably, while coal is omitted from the above list, nuclear (new nuclear power plant at Hinkley Point in the UK) appears to fit into this low-carbon distributed energy future.

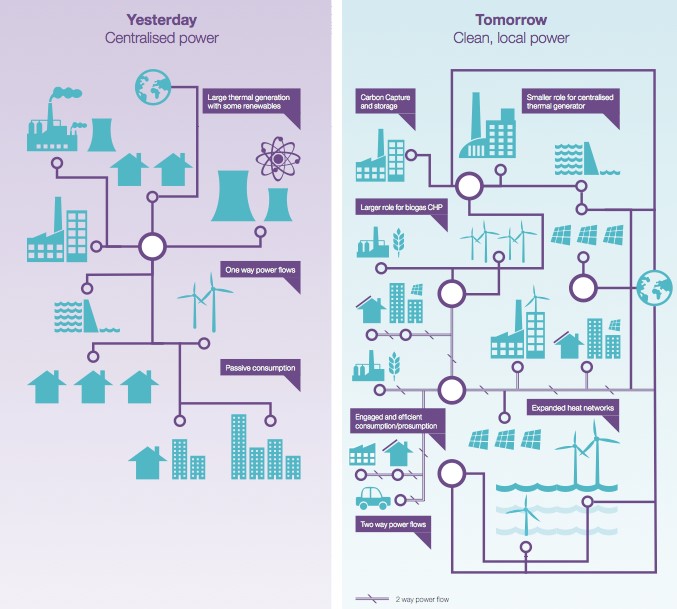

Most importantly, more demand side participation (DSP) – identified in the graphic below as “two way power flows” – for balancing the grid becomes a hallmark of this vision. Consequently, electricity generated predominantly by large thermal power plants and transported via a network of high-voltage transmission lines to distributors – the electricity transmission system operators (TSOs) – which then “transport the electricity through the medium voltage distribution network to industrial consumers, and finally down the low voltage network to household and commercial consumers,” would be a thing of the past. Here, the report stresses that the current grid infrastructure was “designed to function for this step down one-way power flow” only, which now tends to inhibit change due to the anticipated costs even though solutions are feasible.

Distributed Energy – “Thousand Flowers” Transition Pathway  Source: Realising Transition Pathways, Research Consortium ‘Engine Room’

Source: Realising Transition Pathways, Research Consortium ‘Engine Room’

Nevertheless, it is crucial to understand that the incumbent major stakeholders – utilities – do not become obsolete themselves because – as the researchers correctly emphasize – they need “to continue to build and maintain the necessary transmission level assets to meet the demand not generated by the civic energy sector.” Additionally, the report suggests that “[a]long with distributed generation technologies this pathway relies on significant per capita demand reduction [which] requires effective changes in end-user behavioural patterns and a significant uptake of energy efficient measures alongside energy efficient technological diffusion.” Consider this requirement also in light of the growing electricity demand associated with the trend toward ‘Internet-of-Things’ applications, their instrumentation and extra electronic equipment.

Read the entire report here and, in particular, check out Table 8 (Options for Centralized Generation) exploring the alternatives for meeting the need to maintain the necessary transmission-level assets and some of the likely pitfalls.