Supporters of coal have called the planned new rules from the EPA on CO2 emissions from coal-fired power generation a war on coal and have pledged to fight the rule-making process. It is true that there will almost certainly not be a new coal-fired electric generating station built in the U.S. for at least the next several years, but the hiatus won’t be caused by any specific rule. The real danger to the coal industry is uncertainty.

Investing in the electric business is about long stable returns. Electricity assets last a long time, are expensive to install, and are typically expected to provide long-term stable, if modest, returns. Since returns are spread over a long period and are stable, with limited upside (10x returns on energy infrastructure don’t exist) investors and lenders require a quantifiable and manageable amount of risk. Uncertainty in any form makes the quantification and valuation of risk in an electric generation investment much more difficult (or impossible) and severely limits investor interest.

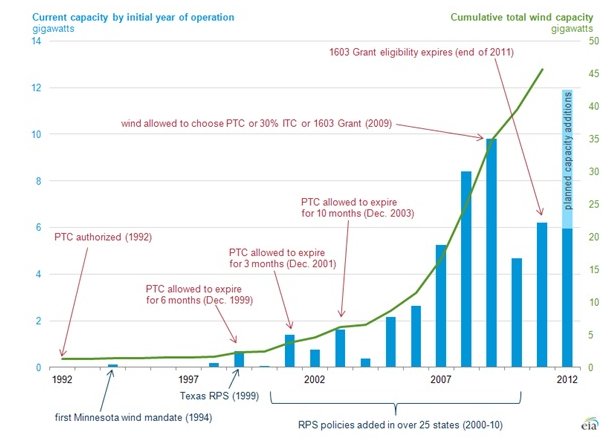

An excellent illustration of the impact of uncertainty on electric generation investment is a recent history of the wind industry. Despite a pattern of consistent, and even retroactive extensions, the uncertainty created by the political fight over extending the Production Tax Credit for wind power has caused nearly complete cessation of new wind facilities being brought on line each time the credit wasn’t extended well in advance of expiration.

The impact of the PTC on the economic case for a wind project has been substantial and was (and still is for some projects) the difference between a profitable and an unprofitable project, so the uncertainty regarding the availability of the credit was a threshold requirement for an investor. An investor simply could not have certainty that it could earn the necessary return (or in most cases any return) without realizing value from the credit, so no investments were made. The result of this uncertainty in 1999, 2001 and 2003 is stark, as investment dropped precipitously from year to year, even though any project would have qualified for the credit because of retroactivity of the extensions.

The challenges for the wind industry have been the result of unstable subsidies – the lack of availability of the PTC was (and as we race towards another sunset, is) a fixed, defined reduction in revenue of about 2 cents per kwh produced from the project (the credit is indexed for inflation and is currently 2.2 cents per kwh). While the subsidy is important, and a significant addition to most wholesale power prices in the US it is also a clearly definable amount. As the credit was again set to expire at the end of 2012 investment slowed, but given that some projects may now be break-even or better without the PTC and because the potential impact of the PTC not being available was limited to the amount of the credit some projects could engage investors despite this uncertainty because the associated risk is quantifiable and therefore manageable.

The challenge for coal generation projects to attract investors and lenders in light of the forthcoming rules on CO2 emissions is more severe. By directing the EPA to draft rules on regulating CO2 emissions from power plants, the White House has sent a clear signal that there will be an economic impact on coal-fired electric generation (and to a lesser extent gas fired generation). What is unclear until the rules are finalized is how significant that economic impact could be. The consensus is that the effect will be significant, but that could mean anything from a material yet measurable impact on potential returns to an economic effect so severe that new investment in coal generating assets is completeley unviable.

Against that uncertainty it is virtually impossible to have confidence that an investment in a coal-fired power plant is an economically good decision – the potential effect of the regulation isn’t defined so the impact could shave a percent from returns, or could absorb all of the potential returns and even cut into the return of capital invested. The trade between risk and return simply can’t be evaluated, and investors and lenders remain risk-sensitive following the financial crisis.

The ongoing market pressure (and uncertainty) caused by relatively low natural gas prices acts as a multiplier on the impact of uncertainty from expanded application of the Clean Air Act. Thermal coal as a source of electric generation has already declined significantly due to earlier regulations and has been accelerated by competition from low-cost natural gas and renewables over the past few years. Even as gas prices rise, the baseline potential economic advantage for coal over gas (and for that matter wind) will remain marginal, and with the adjustment for regulatory uncertainty investors will have easy alternatives to pursue.

There is an important secondary effect of uncertainty on investment. Some investors and lenders will simply not look at a market segment where there is this kind of uncertainty overhang, which reduces the number of potential investors, and in turn makes investments more difficult to obtain and more costly. This “segment avoidance” effect is much worse for less established industries where it acts as an additional barrier for new investors from entering a market. The biofuels industry and the uncertainty from the Renewable Fuels Standard is an example of this – despite a growing industry with potentially good deals to be had many investors won’t even take the time to learn enough to quantify the risk of the program uncertainty. Instead they will wait for the uncertainty to resolve before making a decision on whether to commit to the industry. In the case of coal generation it has been a historically well-served market by the financial community, and so there are still many sophisticated investors and lenders that could be drawn into the market. However, as time passes, that community will shrink leaving fewer and fewer potential investment partners.

If uncertainty is damaging, what is potentially devastating to the industry is that there is almost certainly no fast resolution with this uncertainty overhang persisting for years. A long protracted legal fight over how the rules will be written and enforced is assured.

I spent some time discussing the rule making process with my colleague Jeff Karp, who spent more than a decade on environmental and enforcement inside the federal government. “Given the magnitude of the stakes – the economic viability of the entire coal sector” finalizing the rules is “certainly a long way off and unlikely to actually occur while the present Administration still is in office.” Curiously, the fight being waged by coal supporters may actually be making the industry position worse by extending this period of uncertainty. A better solution would almost certainly be to find some legislative compromise, possibly built around a broader Congressional compromise on greenhouse gas emissions, which could be more nuanced or gentle in its implementation (though how this would come together in light of the current atmosphere in Congress is unclear). Instead, the rule-making process will force this long period of regulatory uncertainty.

Irrespective of the timing and structure of the final emission rules, the power sector in the U.S. will be permanently altered. It will not be the actual rules, rather this period of uncertainty as the legal and political battles play out, that will make that declining share for coal steeper and permanent. The final version of the rules will likely be of little relevance, as the uncertainty of the rule-making process will immediately frighten away potential investors. This loss of outside capital for large expensive projects will effectively cease all new development of thermal coal generation and will also significantly hamper upgrade investments at existing facilities forcing an acceleration of retirements.

Republished with permission from Energy Trends Insider