Forget about the LED lighting and the R-38 ceiling insulation. The way to drive down electricity use is to put on massively popular sporting events that draw people together to watch in large groups, and to time the events to take place when folks would typically be doing stuff around the house.

That’s the slightly tongue-in-cheek – or maybe it’s hopeful – message from Opower, the energy report and analytics company.

Using data from 18,000 households served by the British power company First Utility, Opower looked at electricity-use patterns during three big televised sporting events this summer – the June 24 England vs. Italy European Cup quarterfinal; the Wimbledon final on July 8; and the July 27 Olympics Opening Ceremony – and found big departures from normal usage.

The Sunday afternoon Wimbedon final, with the popular Scot Andy Murray taking on Roger Federer, coincided with energy use 7 percent greater than on a typical Sunday afternoon, Opower said.

During the England-Italy match, on a Sunday evening, electricity use was down throughout the 7:30-10:30 p.m. telecast, which drew an audience of up to 23.2 million. In one half-hour period during the match, electricity use was 10 percent below normal. Then when the match ended, electricity use shot up, to 5.3 above normal.

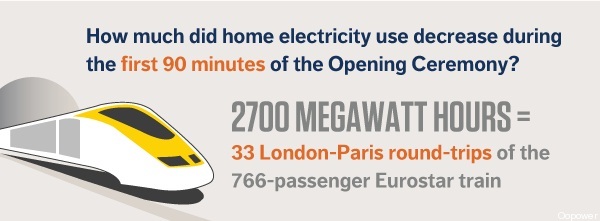

Then there was the Opening Ceremony. From 9 p.m. to 10:30 p.m., the first half of the ceremony, Brits used 7.4 percent less electricity than usual; but in the following time frame, up until midnight, energy use was 5.1 percent above normal.

Up, down, and all around – is there any rhyme or reason to this? There is, Opower says, linking the variations from normal to the timing of the events, as well as the power of the event to draw big groups together for communal viewing.

The Wimbledon final, you see, was on a Sunday afternoon when electricity is typically low – presumably because people tend to be out of the house. “The Andy Murray final changed that pattern,” Opower says. “Millions of Brits who would have been outside of their homes were instead glued to the tube and consuming electricity at home that they otherwise would not have.”

The Euro 2012 match was pretty much the opposite story: Instead of people being at home – cooking dinner, doing laundry, watching TV – folks had gathered around the television in big groups to watch soccer. Lots of eyeballs were focused on a smaller number of televisions, while fewer than normal people were doing the usual power-guzzling activities. That led to the electricity-use decline. But immediately after the match was over – Italy won on penalties – instead of being tucked away in bed, “many folks were likely consuming electricity into the later hours – watching post-game lowlights, stublbing in late from the pub, or melancholically drinking a cup of boiled tea in an illuminated kitchen.”

Likewise the Olympics. During the first half of the ceremony, “many households were not actively using appliances other than their TV.” Heck, 50,000 people were in Hyde Park watching the game on one huge screen, and the pubs were packed. Then by staying up later than usual, they used more power than typical late in the ceremony.

Opower preferred to focus on the former, energy-conserving effect, endorsing the idea of “TV-Pooling.” You know, kind of like car-pooling.

“Communal TV viewing may at first seem like a trivial concept, but its effect on a country’s residential energy consumption could be significant. If TV-Pooling resulted in residential electricity consumption decreasing by 5 percent for two hours every Sunday night … that would be equivalent taking 23,000 homes of the U.K. grid each year,” Opower wrote.